- Home

- Eduardo Sacheri

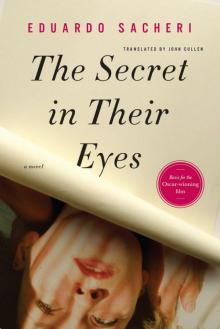

The Secret in Their Eyes

The Secret in Their Eyes Read online

Copyright © 2005 Eduardo Sacheri

Originally published in Spanish as La pregunta de sus ojos

Translation copyright © 2011 John Cullen

Production Editor: Yvonne E. Cárdenas

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from Other Press LLC, except in the case of brief quotations in reviews for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper, or broadcast. For information write to Other Press LLC, 2 Park Avenue, 24th Floor, New York, NY 10016.

Or visit our Web site: www.otherpress.com

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Sacheri, Eduardo A. (Eduardo Alfredo), 1967-

[Pregunta de sus ojos. English]

The secret in their eyes / by Eduardo Sacheri; translated by John Cullen.

p. cm.

Originally published in Spanish as La pregunta de sus ojos.

eISBN: 978-1-59051-451-1

1. Detectives—Argentina—Buenos Aires—Fiction.

2. Murder—Investigation—Fiction. 3. Buenos Aires

(Argentina)—Fiction. I. Cullen, John, 1942- II. Title.

PQ7798.29.A314P7413 2011

863′.7—dc22

2011013294

PUBLISHER’S NOTE:

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

v3.1

To my grandmother Nelly

for teaching me

how valuable it is

to preserve and share

memories.

Translator’s Note

At the time of the novel, the Argentine judiciary was divided into two jurisdictions, investigative courts and sentencing courts. Judges—examining magistrates—presided over investigative courts, and every judge’s court comprised two clerk’s offices. A clerk employed about eight people, of whom the second in command was the deputy clerk and chief administrator, the position held by this novel’s protagonist, Benjamín Chaparro.

A period of great turbulence in Argentina culminated in the so-called Guerra Sucia, the Dirty War, which lasted from 1976 to 1983. During these years, the Argentine state was the chief sponsor of massive and systematic political violence, whose victims included not only members of armed guerrilla groups such as the Montoneros, but also students, activists, trade unionists, teachers, journalists, and leftists in general. In such an unstable and dangerous environment, even the basically apolitical Chaparro is at risk. State terrorism in Argentina during the Dirty War resulted in the disappearance of at least 13,000 people; some estimates run as high as 30,000.

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Translator’s Note

Retirement Party

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Cinema

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Telephone

Alibis and Departures

Archive

Seamster

Pages

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

First and Last Names

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Abstinence

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Coffee

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

More Coffee

Doubts

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

More Doubts

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Restitution

Author’s Note

About the Author

About the Translator

Retirement Party

Benjamín Miguel Chaparro stops short and decides he’s not going. He’s not going, period. To hell with all of them. Even though he’s promised to be there, and even though they’ve been planning the party for three weeks, and even though they’ve reserved a table for twenty-two at El Candil, and even though Benítez and Machado have announced their willingness to come from the ends of the earth to celebrate the dinosaur’s retirement.

He halts so suddenly that the man walking behind him on Talcahuano toward Corrientes barely manages to avoid a collision, dodging past with one foot on the sidewalk and one on the street. Chaparro hates these narrow, noisy, light-deprived sidewalks. He’s walked on them for forty years, but he knows he’s not going to miss them after Monday. Not the sidewalks and not a great many other things in this city, where he’s never felt at home.

He can’t disappoint his colleagues. He must go, if only because Machado is coming all the way from Lomas de Zamora just for the occasion, despite his bad health and advanced age. And Benítez likewise. It’s not a terribly long way from the Palermo neighborhood to Tribunales, but the fact is that the poor old guy’s pretty much a wreck. Nevertheless, Chaparro doesn’t want to go. He’s sure about very few things, but this is one of them.

He looks at himself in the window of a bookstore. Sixty years old. Tall. Gray-haired. Aquiline nose, thin face. “Shit,” he feels obliged to conclude. He scrutinizes the reflection of his eyes in the glass. A girlfriend he had when he was young used to make fun of his compulsive way of looking at himself in shop windows. Chaparro never confessed the truth, neither to her nor to any of the other women who passed through his life: his habit of gazing at his own reflection has nothing to do with self-love or self-admiration; it’s never been anything but another attempt to figure out who the hell he is.

Thinking about that makes him even sadder. He sets out again, as if motion could save him from being pricked by the barbs of this new, additional sadness. From time to time, walking without haste on that sidewalk forever untouched by the afternoon sun, he checks himself in the shop windows. Now he sees the sign for El Candil, up there on the left, across the street and thirty meters on. He looks at his watch: 1:58. Almost all of them must be there by now. He himself sent off the people in his department at 1:20 so they wouldn’t have to run. The coming court session doesn’t begin until next month, and they’ve already closed and archived the cases from the previous session. Chaparro is satisfied. They’re good kids. They work hard and learn quickly. The next thought in the sequence is I’m going to miss them, and as Chaparro refuses to squelch around in nostalgia, he comes to a stop again. This time, there’s no one behind to crash into him, and the people coming his way are able to navigate around the tall man in the blue blazer and gray trousers who’s now looking at himself in the window of a lottery office.

He turns around. He’s not going. He’s definitely not going. Maybe, if he hurries, he can catch the judge before she leaves

for the restaurant, because he knows she stayed behind to finish an order for someone’s release from preventive detention. It’s not the first time the idea has occurred to him, but it is the first time he’s summoned the modicum of courage needed to act on the idea. Or maybe it’s just that the other prospect—the prospect of attending his own retirement luncheon—corresponds to his notion of hell, and he wants to avoid infernal torments. Him, sitting at the head of the table? With Benítez and Machado beside him, forming a trio of venerable mummies? Listening to that pathetic de Álvarez pose his traditional question—“Let’s do it Roman style, all right?”—so that he can spread around the cost of some high-end wine and knock back most of it himself? Or Laura, asking everybody in sight to split a portion of cannelloni with her so she won’t stray too far from the diet she just started last Monday? Or Varela, meticulously descending into his trademark alcoholic melancholy, which will move him to tears as he embraces friends, acquaintances, and waiters? These nightmarish images make Chaparro increase his pace. He goes up the courthouse steps from Talcahuano Street. They haven’t closed the main door yet. He jumps into the first available elevator. There’s no need for him to tell the operator he’s going to the fifth floor; in the Palace of Justice, the very stones know him.

With resolute steps, the soles of his tan loafers resounding on the black and white floor tiles, he walks along the corridor parallel to Tucumán Street until he stands before the tall, narrow door of his court. He hesitates mentally over the possessive “his.” Yes, why not? It’s his, it belongs to him much more than to García, the clerk, or to any of the other clerks who preceded García, or to any of those who’ll succeed him.

While he’s busy with the lock, his immense bundle of keys jingles in the empty corridor. He closes the door behind him rather forcefully, letting the judge know that someone has come in. Wait a minute: Why “the judge”? Because she’s a judge, sure, but why not “Irene”? Well, just because. He’s got enough with asking for what he’s going to ask for without the extra burden of knowing that he must address his request to Irene and not simply to Judge Hornos.

He knocks softly twice and hears her say, “Come in.” When he steps into her office, she’s surprised, and she asks him, “What are you doing here?” and “Why aren’t you at the restaurant already?” In posing these questions, she uses the familiar tu form—or, to be more precise, since they’re in Buenos Aires, the familiar vos form—but Chaparro wants to avoid getting bogged down in forms of address, because those, too, can be a source of confusion, liable to sabotage his clear intention to make the request he decided to make outside on Talcahuano Street, not far from Corrientes Avenue. And it’s disheartening that this woman’s presence throws him into such turmoil, but in a spasm of self-discipline, Chaparro concludes that there’s nothing for it, that he absolutely, definitely, totally, must cut short the process of psyching himself up, stop screwing around, and make, once and for all, the request he’s come to make. “The typewriter,” he says, blurting it out with no preamble. Brute, wretch, oaf. No subtle lead-ups. Nothing like You know what, Irene, I was thinking that maybe, that in one of those, that it could be that, or what would you say if, or any other colloquial formula that might serve to avoid precisely the look Chaparro sees on Irene’s face, or the judge’s, or Her Honor’s, that perplexity, that uncomprehending speechlessness caused by surprise at his abrupt manner.

Chaparro realizes he’s put his foot in it, not for the first time. He backs up to the beginning and tries to respond to the question madam asked him in the first place, the one about the retirement luncheon, at which, considering what time it is, they must be paying tribute to him right now. He tells her he’s afraid of getting maudlin and nostalgic, afraid he’ll wind up talking about the same old things with the same old people and dissolving into pathetic melancholy, and since he looks into her eyes as he tells her all that, there comes a moment when he starts to feel his stomach sinking toward his intestines and a cold sweat breaking out on his skin and his heart turning into a snare drum. Because this emotion is very deep, very old, and very useless, Chaparro dashes back into the outer office to close the window, thus peeling himself away, as best he can, from those dark brown eyes. However, the window is already closed, so he decides to open it, but then a blast of cold air makes him decide to close it again. In the end, he has no alternative but to return to Irene’s office, prudently remaining on his feet in order to avoid any obligation to look at her directly as she sits at her desk with the file open in front of her. She follows his movements, his looks, and the inflections of his voice with the same very attentive attention she’s always given him. Chaparro shuts up for a while, knowing that if he keeps on going down that path he’ll end up saying irreparable things, and then, just in time, he returns to the subject of the typewriter.

Although he has no idea what he’s going to do from now on, he tells her, he’d love to take a stab at his old project of writing a book. As he speaks the words, he feels like a fool. An old man, twice divorced, now retired, and he thinks he’ll be a writer. The post-retirement Hemingway. The García Márquez of Buenos Aires’s western suburbs. To make matters worse, Irene’s—or, preferably, the judge’s—eyes sparkle with sudden interest. But he’s already gone too far to turn back, and therefore he expatiates a little on his desire to try writing, it’s something he’s wanted to do forever, and now he’ll have more time, so maybe, why not. And this is where the typewriter comes in. Chaparro feels more comfortable, because here he’s treading on firmer ground.

“As you can guess, Irene, at my age I’m not going to learn how to use a computer, you know? And I’ve got that Remington in my fingers like a fourth phalange.” (Fourth phalange? Where does such idiocy come from?) “I know it looks like a tank, and it’s got that minuscule ribbon, and it’s olive green, and it makes a sound like artillery fire every time you hit a key, so I’m taking a chance and hoping no one will need it, and naturally it would only be a loan, absolutely, a couple of months, three at the most, because believe me, I’m not up to writing a very long book, as you may imagine” (and there he is again, doing his self-deprecation number). “And besides, all the new kids use computers, and there are three other old typewriters stored on the top shelf, and if you need it, you can always let me know and I’ll bring it back here,” Chaparro declares, and he’s not through.

But he stops talking when she raises a hand and says, “Don’t worry about it, Benjamín. Just take it, it won’t be a problem. It’s the least I can do for you.”

Chaparro swallows hard, because that “you” at the end, the vos reserved for family and friends, sounds very familiar and friendly indeed, and then there’s the tone she’s using, the one she uses on certain occasions, occasions that have been engraved, one by one, in his memory, bright feverish slashes in the monotonous horizon of his solitude, despite the fact that he’s dedicated almost as many nights to forgetting them, or trying to forget them, as he has to remembering them, and therefore he finally gets to his feet, thanks her, gives her his hand, accepts the fragrant cheek she offers him, closes his eyes while he grazes her skin with his lips, as he always does when he has a chance to kiss her—with his eyes closed, he can concentrate better on the innocent, guilty contact—practically runs into the small adjacent office, picks up the typewriter with two rapid movements, and escapes through the tall, narrow door without looking back.

He retraces his steps along the corridor, which is even emptier now than it was twenty minutes ago, takes elevator number eight to the main floor, goes down the hall toward Talcahuano, exits by the side door with a nod to the guards, walks up to Tucumán Street, crosses it, waits five minutes, and climbs, as best he can, onto the 115 bus.

When the bus turns the corner at Lavalle, Chaparro twists his head around to the left, but of course at this distance he can’t see the sign for El Candil. By now, Irene—or rather, the judge—must be walking to the restaurant, where she’ll explain to the others that the guest of honor has ski

pped out. It won’t be so bad—they’re all gathered together, and they’re hungry.

He pats his rear trouser pocket, pulls out his wallet, and puts it in the inside pocket of his jacket. He’s never had his pocket picked in his entire forty-year career, and he has no intention of being ripped off for the first time on his last day in Tribunales. Walking as fast as he can, he reaches the Once railroad station. The next train is leaving on Track 3, bound for Moreno and making all stops in between. In the train’s last three cars, the ones closest to the platform entrance, all the seats are occupied, but from the fourth car on, Chaparro finds many available places. He wonders, as he always does, if the passengers standing in the crowded rear cars choose those spots because they’re getting off soon, because they’ve been sitting all day and want to stretch their legs, or because they’re stupid. Whatever their reasons, he’s grateful. He wants to sit in a window seat on the left-hand side, where the afternoon sun won’t bother him, and think about what the hell he’s going to do with the rest of his life.

1

I’m not sure about my reasons for recounting the story of Ricardo Morales after so many years. I can say that what happened to him has always aroused an obscure fascination in me; perhaps the man’s fate, a life destroyed by tragedy and grief, provided me with a chance to reflect on my own worst fears. I’ve often caught myself feeling a certain guilty joy at the disasters of others, as if the fact that horrible things happened to other people meant that my own life would be exempt from such tragedies, as if I’d get a kind of safe-conduct based on some obtuse law of probability: If such and such a catastrophe befalls Joe Blow, then it’s unlikely that it will also strike Joe’s acquaintances, among whom I count myself. It’s not as though I can boast of a life filled with success, but when I compare my misfortunes with what Morales suffered, I come out well ahead. In any case, it’s not my story I want to tell, it’s Morales’s story, or Isidoro Gómez’s, which is the same story but seen from the other side, or seen upside down, or something like that.

The Secret in Their Eyes

The Secret in Their Eyes